Stone Dust and Surrender

Listening to the Light

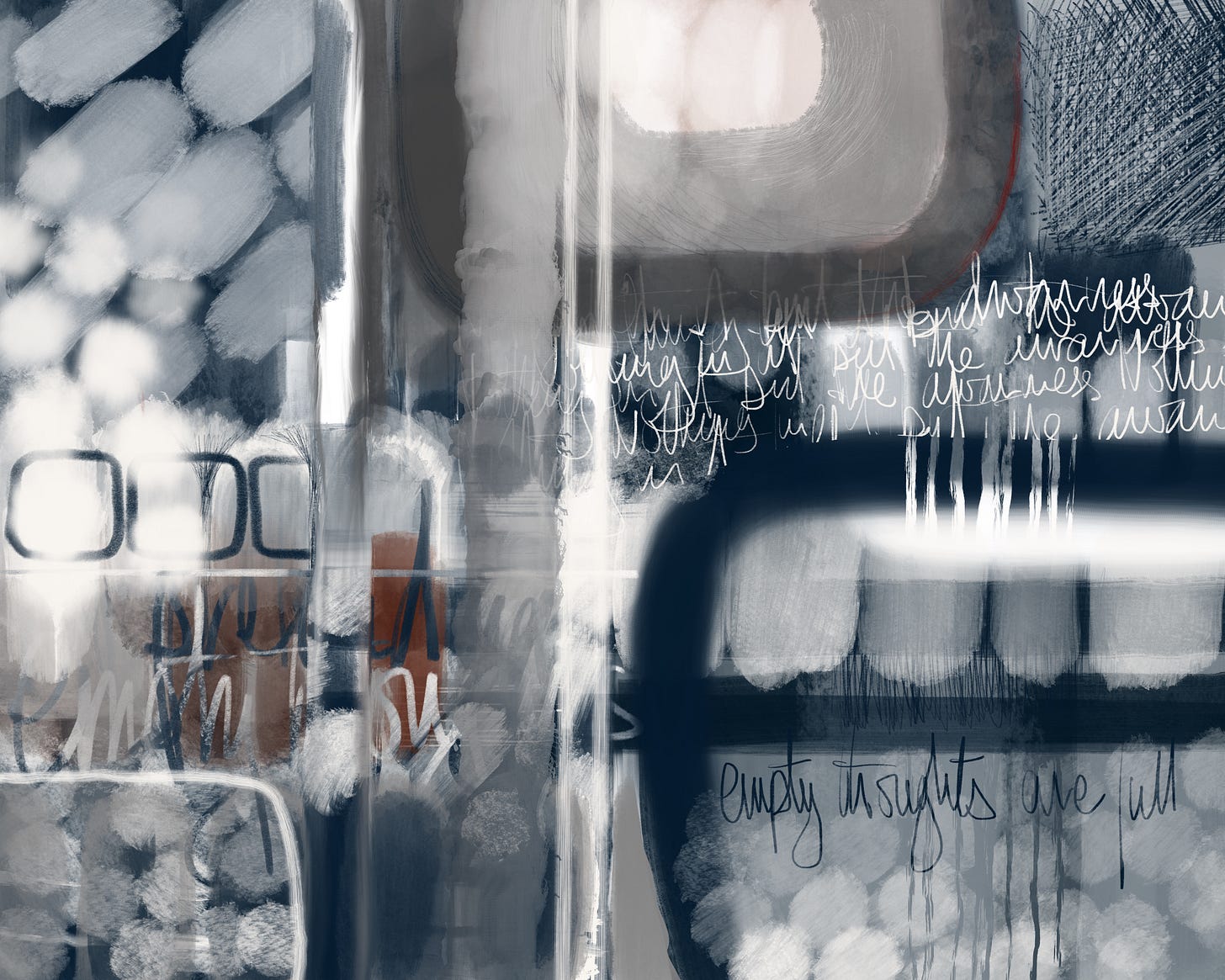

Empty Thoughts are Full - 30 x 24 in

Medium: Painted on iPad Pro

“This is a reflection from From London to Mexico, a book in progress about the quiet signs that guide us into unexpected change.”

Does anyone talk about that part?

There’s a strange kind of emptiness that follows achieving something you were sure would open doors for you.

I’d worked hard for my Bachelors degree in Sculpture. At the time, I thought it would stand for something. Maybe you’ve had that feeling too; that strange gap between expectation and reality, when you suddenly realise there’s no clear next step, and no one waiting to show you the way.

In 1992, I stepped out of art school into a world with no survival guide. No real sense of where I fitted into the industry.

That was partly my doing. I wasn’t mature enough at the time to recognise or seize the opportunities that did exist. It never dawned on me that I’d need to learn how to promote myself, or how to begin navigating the art world as a practising artist. In retrospect, I’d have chosen a course that included this element, and I would have benefited enormously from connecting with an established artist who was already doing the work.

A number of the more experienced students, or those with existing connections, had already set up links to previous or potential work experience. They seemed to know how to position themselves, how to make the transition from student to working artist. I didn’t. I was still hoping the work would speak for itself.

Still, I gave it everything I had. I exhibited here and there. I made a few sales. There were moments of possibility. But it wasn’t enough—not financially, and certainly not emotionally. The work became isolating. The silence around it began to close in: thick and airless. Not the rich silence of absorption, but the hollow kind that echoes back at you.

I should say that the work itself wasn’t the problem. In many ways, I loved it. I was absorbed, physically engaged, and there were moments of real presence. But that didn’t cancel out the deeper isolation. There was no structure around me, no feedback loop, no one really seeing what I was trying to do. That’s the kind of silence I’m talking about. Not the quiet of focus, but the kind that starts to press in from the outside.

To get to my studio in Southwark, South East London, I used to set off early on my motorbike. It was a thirty-minute ride from Earlsfield, where I shared a flat with a few other ex-Wimbledon students. London was wonderful in the early hours; quiet, expectant, still holding the cool of night.

I always enjoyed those journeys. There was a sense of freedom and possibility: a kind of meditation, really. I’d be so intensely immersed in the process of riding, all my senses at their sharpest. It was a solitary journey, but one I connected with. I felt completely at one with the busy world around me.

Once in the studio, the atmosphere shifted. A different kind of silence. I’d often be one of the only artists there at that hour. If I passed someone else, we’d exchange the usual nod and eye contact that spoke a hundred words.

I remember the excessive layers I had to wear to keep warm. When I carved stone, I had to work outside in the yard, since the noise of chipping away would have been too disruptive for the other artists working in quieter mediums. The work was hard, dusty. I wore a mask and was covered in stone dust most of the day. It got everywhere: ears, nose, eyes… and, if I’m honest, places where the sun don’t shine.

But despite the austere environment, I felt I was where I was supposed to be.

At lunchtime, I’d sit with a flask of tea and a simple sandwich that tasted much better than it was.

Maybe you’ve had a place like that too. Somewhere rough around the edges, but where something inside you came quietly alive.

Even then, as I worked alone in my studio, I wasn’t just trying to make objects. I was trying to understand something. I carved into stone, cutting away at what was solid. I modelled clay and plaster, pressing form into being with my hands. Each gesture was a negotiation: taking away, adding, reshaping… trying to reach toward something that lived beyond the material surface.

My early sculptures were figurative, inspired by the ten states of being described in the teachings of T’ien T’ai: from the depths of hell to realisation and Buddhahood. I was trying to give shape to something invisible—the emotional, psychological, and spiritual terrain of human life.

Already at that time, without fully realising it, I was reaching toward something unseen; a deeper current within the human condition. I didn’t have the words for it yet, but my hands were searching. The smell of stone dust, the cold texture of plaster, the stubborn resistance of wood under the blade… they were all part of that search.

I didn’t have the words for it at the time. I was just working, just trying to make sense of something. But in hindsight, maybe that’s how it starts for most of us. Not with clarity, but with a quiet pull towards something we don’t yet understand.

That silent work, I now realise, marked the beginning of an unexpected transition on my spiritual path.

The medium has shifted over the years, but the essence hasn’t. When I returned to painting decades later in Mexico, I found myself drawn to the same invisible questions. Instead of controlling, cutting, and modelling form, I try to let it flow… without resistance, without force… allowing whatever is ready to appear on the canvas.

While I had been a practising Buddhist for years, it was through those early sculptures—and later, my abstract paintings—that a quieter truth began to surface. They revealed something I hadn’t quite grasped, even after all the chanting, meditation, and spiritual seeking. The heart of it wasn’t in the striving, or even in the stillness; it was in the surrender—not of effort, but of control over how things should turn out.

Learning to surrender willingly was a huge shift for me. Before moving to Mexico, I clung tightly to plans, outcomes, and the illusion that I was steering the ship.

People often assume that living in the Caribbean is what brought me peace. But the truth is, the real change wasn’t in the scenery. It was in the slow, quiet, internal letting go. The more I surrendered, the more the world seemed to rearrange itself in response.

And yes, I now live in “paradise.” Though it’s worth noting that surrendering is significantly harder when you’re being eaten alive by mosquitoes, sweating through your clothes, swatting sand flies, dodging snakes, and side-eyeing the occasional tarantula or scorpion. Still, I try to remember all that the next time I’m sipping a mezcalita with my feet in the sand and the crystal-clear waters lapping at my toes.

Presence, after all, comes with texture.

Looking back now, I can see how much of this was already beginning in that dusty, echoing studio in the early ’90s. I just didn’t know it yet. In retrospect, the real education was never going to be about fitting into the industry. It was about learning how to listen: first with my hands, then with my whole self.

Author’s Note

Even when I look back on what once felt like failures, missed opportunities, or just plain bad luck… I have no regrets. The truth is, the universe gave me what I needed, not always what I thought I wanted. And it still does.